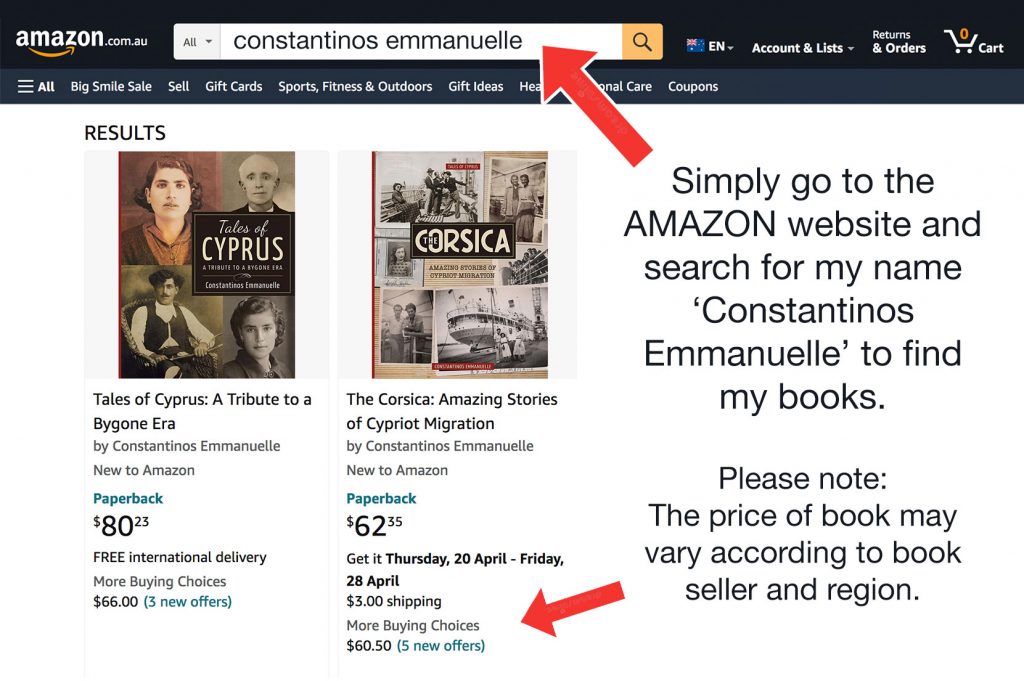

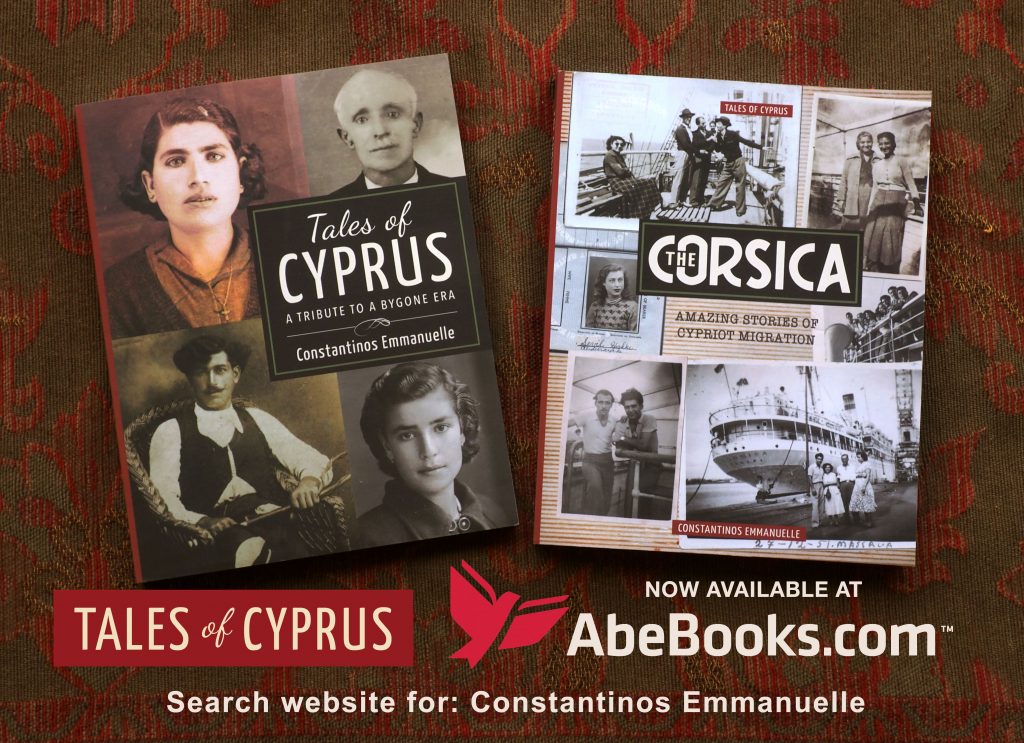

Hi everyone. I am pleased to announce that BOTH of my books are now available online through AMAZON and Abebooks. Simply go to the Amazon and Abebooks website and search for my name ‘Constantinos Emmanuelle’ to find them. Please Note: These are paperback editions and the price, delivery charges and shipping times may vary according to the book seller and region. The books are printed via IngramSpark which is a ‘print-on-demand’ publishing company.

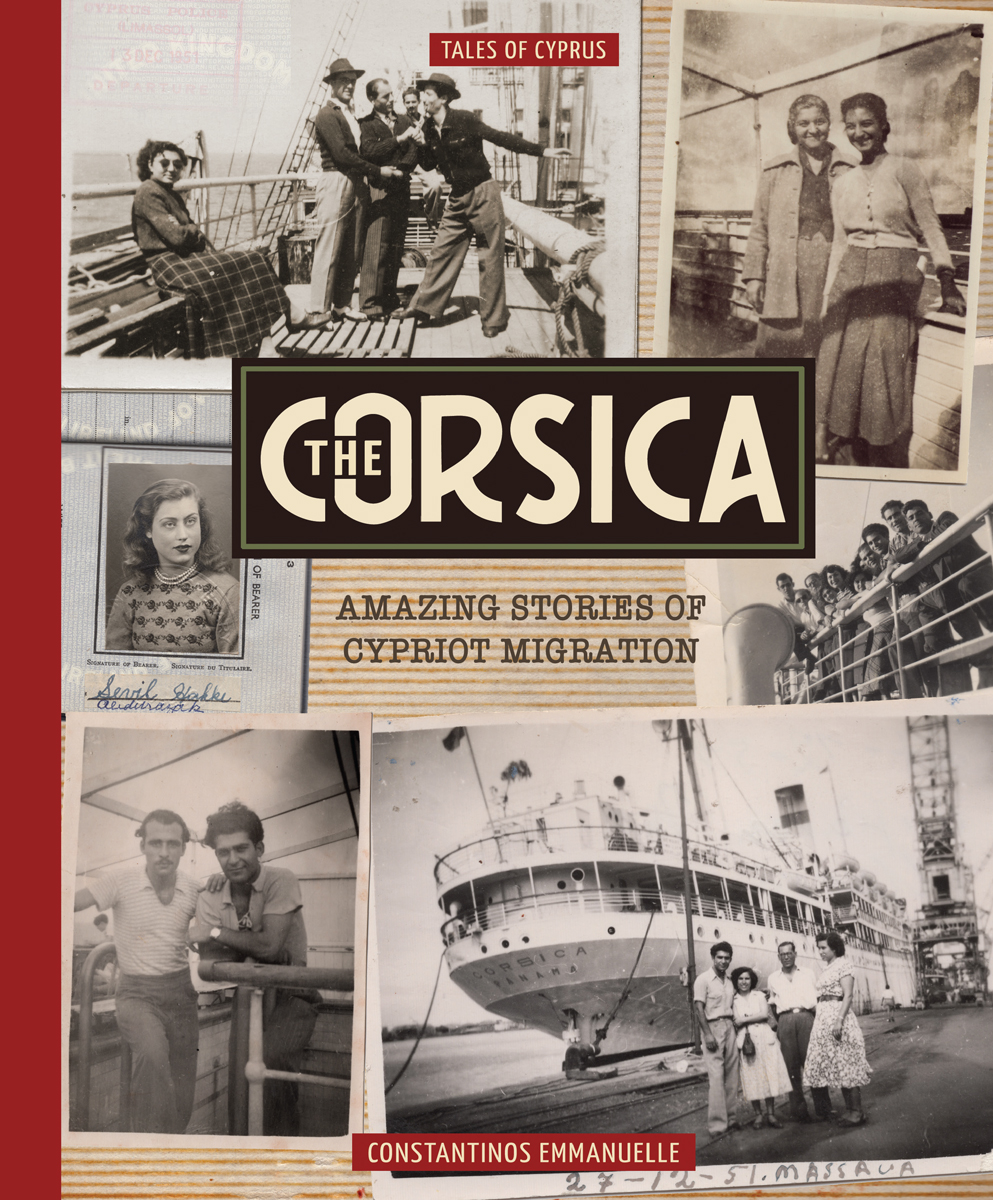

The Corsica: Amazing stories of Cypriot migration

This is my second book for Tales of Cyprus. In this book, I explore the infamous and harrowing journey of a migrant ship called the Corsica and its maiden and only voyage from Cyprus to Australia in 1951. The majority of the interviews I have conducted over the years for Tales of Cyprus have been with Cypriots who left their island home to migrate to other countries. This mostly occurred after the Second World War with people desperate to escape poverty and financial hardship . They left Cyprus to seek their fortune and perhaps a better life in foreign countries like Australia. Most of these people were born in the 1920s and 30s so by the time I got to meet them and record their stories, they were aged in their eighties and nineties.

During the course of my interviews, a ship called the Corsica kept popping up. I soon discovered that this was no ordinary migrant ship and no ordinary migrant journey. Of course, there were other ships mentioned such as the Cyrenia, Hellenic Prince, Misr, Ana Salen, Surriento and Castel Felice – but no other ship seemed to stir as much emotion in my interviewees as the Corsica. This may have been because it was so dilapidated and unsuitable for passenger travel. As one person stated, “it was the ship from hell.”

In January 1951, the Corsica, (then known as the Liguria), broke down near Fremantle and had to be towed to port where it was arrested and held by the Australian authorities for repairs. It is therefore astonishing, that ten months later, renamed as the Corsica, she was commissioned to bring over 780 unsuspecting Cypriot passengers to Australia. This was the largest group of Cypriot migrants ever to leave the island by ship at any one time. This was also the Corsica’s only voyage from Cyprus to Australia. By comparison the Surriento made twenty-eight voyages and the Cyrenia made twenty-six.

In 2019, I decided to investigate the Corsica further by re-interviewing the Cypriots who had first brought this ship to my attention. Cypriots such as Christos Apeitos, Nicos Jonis, Sevil Abdurazak, Takis Ioannou and Loizos Kyriacou. I then posted a ‘call-out’ on my Facebook page for other passengers of the Corsica to come forward. The response was swift and overwhelming. I spent many, many hours in 2019, travelling and interviewing people who had journeyed on the Corsica.

When the pandemic began in 2020, Melbourne went into one of the strictest and longest lockdowns in the world. Thankfully, I was still able to complete many interviews via Zoom or by telephone. In total I managed to track down seventy-eight passengers who travelled to Australia on the Corsica, of which, fifty-six where selected for this book.

With each story of migration I have tried to include some background information about the passenger, such as their family life, upbringing and schooling. I have also recorded their reasons for leaving Cyprus, their recollections of the journey and some details about their life in Australia soon after migration.

I had always planned to publish this book about the Corsica in 2022 to mark the seventieth anniversary of her journey to Australia. I am so grateful that I have been able to meet and interview so many of the passengers of this voyage before it was too late. The youngest Cypriot I interviewed was seventy-one years old and the oldest was almost one hundred. Given the passage of time since the Corsica docked at Port Melbourne back in February 1952, I had anticipated that my interviewees might struggle to remember details or facts about the journey.

However, this was not the case. All of the passengers I interviewed, remembered the rotten potatoes and onions and the stench on the ship. Most recalled a slow and uncertain journey. They also recalled the poor quality of the food and the absence of fresh drinking water. Given the fallacy of memory, I was careful not to edit the comments made by the passengers. If they said the trip took three months (when it took seven weeks), I left their comment unchanged. If they recalled eating only spaghetti every day – so be it. More than anything, I wanted to preserve their living memories, even though at times, they were at odds with the facts. After all, they are trying to recall events that occurred seventy years ago. Moreso, some of my interviewees had not really discussed or shared their story of migration with anyone, until I came knocking on their door.

Like most of my Tales of Cyprus endeavours, researching the Corsica has been a real eye-opener for me – a real education. I always knew that my parent’s generation were special, but I can now fully appreciate the guts, determination and hope that was shared by these early migrants as they ventured into the unknown. Can you imagine going into debt, just to pay for your ship fare. Or deciding to leave your family and friends, to seek a better life on the other side of the world not knowing if you would ever see each other again? Imagine not knowing the language or the culture of the new country and arriving penniless with no guarantee of finding accommodation or work. One might say it was sheer madness or perhaps, just extraordinary faith and resolve. One thing is for sure – they were a resilient generation.

Throughout my interviews for this book, the word ‘philoxenia’ was mentioned over and over. This word means friendship towards others and hospitality. There are many stories in this book of Cypriots reaching out to help one another.

The earlier migrants jumped at the opportunity to welcome the new arrivals, to ensure that they felt safe and secure in what must have seemed like an alien landscape. I hope you enjoy reading these amazing stories of migration as much as I have enjoyed bringing them out of the shadows of a forgotten past and into our present consciousness.

I am sure that you will agree that the sacrifices made by these early Cypriot migrants have ensured that their descendants will be able to live a richer and better life. They are my heroes.

CLICK HERE TO VIEW MY WALL POSTERS FROM THE CORSICA BOOK LAUNCH!

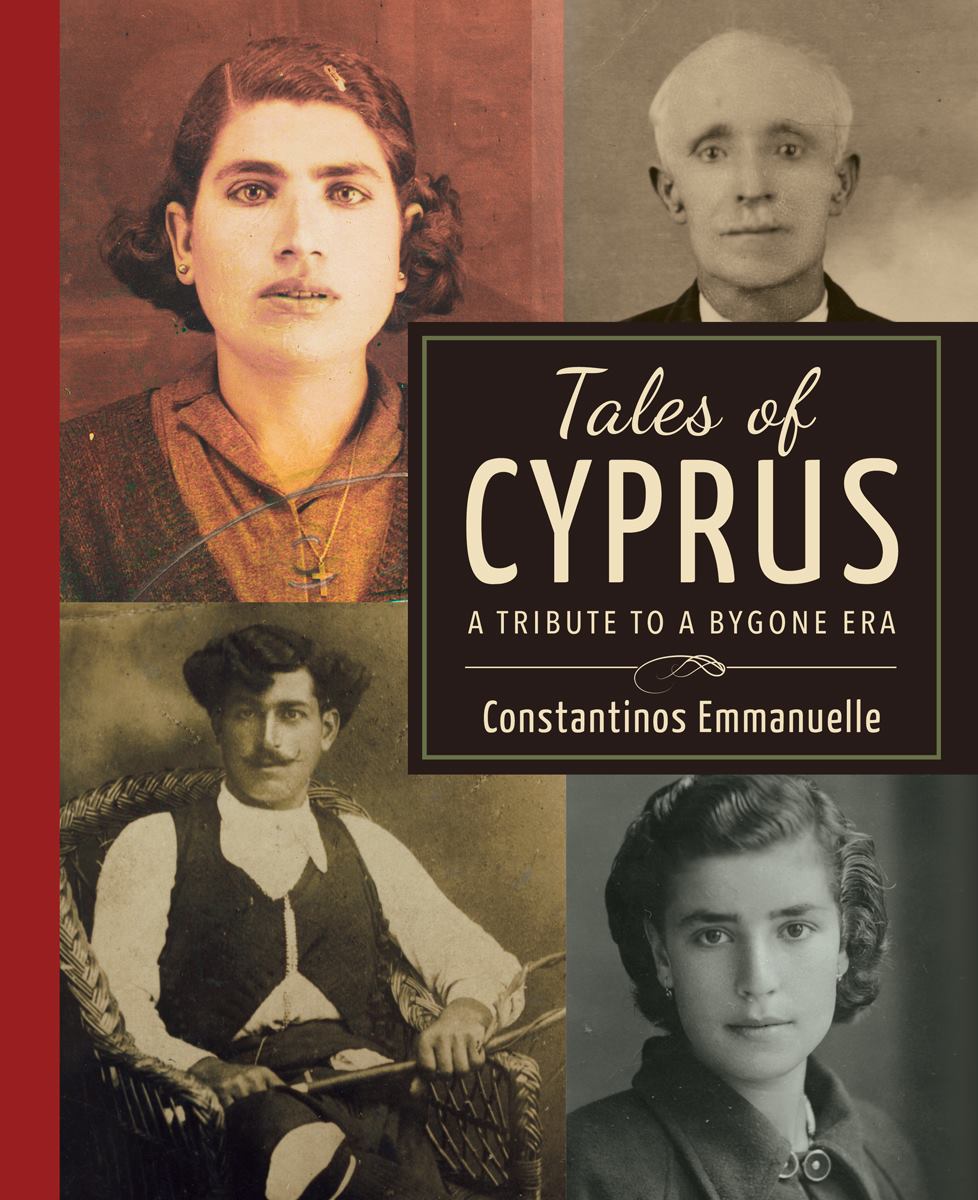

A Tribute to a Bygone Era

A Tribute to a Bygone Era

With this first book for Tales of Cyprus, I had a single-minded ambition to document and preserve the oral histories and living memories of my parents’ generation. When you speak to older Cypriots who remember Cyprus before 1950 you get the sense that they had a simpler, yet wonderful life. Yes, they were poor, perhaps even ignorant, and their life was hard but they seemed content with what they had. Once I realised that Cyprus in the past was a completely different world, I had to go and investigate.

I deliberately chose to focus on the period pre-1950 as I did not want to get into the political issues that arose on the island thereafter. Besides, the political ideology and propaganda that eventually divided Cyprus in 1974 is still furiously contested and I find the ongoing debate very counterproductive. I would much rather discuss the period pre-1950, that I often refer to as the golden era.

It may be rather cliché to admit, but once I became a parent I quickly developed a renewed respect for my own parents. I had been dismissive of their life before then and I never really appreciated that the intricate nature of their mindset was hardwired by their cultural beliefs.

It took a certain maturity for me to realise that both my parents belonged to a special generation and a unique period in time.

The quest to discover my ethnic roots and ancestral home began with a lengthy interview with my father. What a world I discovered. A world far removed from my own, with experiences I knew very little about. Although my father had always shared snippets of his past life with me, it wasn’t until I asked him specific questions that he truly opened up.

My father arrived in Australia in early 1950, after the war, seeking a better life. Three years later, he saw a photo of my mother and decided to bring her over to Australia with the hope of marriage. It was an arranged marriage, which was very common at the time. I have to say they really made it work. There was a respect and tolerance that you seldom see in couples nowadays. No matter how tough their life and their marriage was, my parents never threw in the towel. They never gave up. What fascinated me about my parents’ life and the decisions they had to make was just how accepting they were with everything that happened to them. Compared to my generation, they were from a different planet altogether.

I have been intoxicated by my Cypriot culture from the time I first stepped foot on the island as a young boy. It’s been quite a discovery and adventure ever since. Wandering through the mountains and along the cobblestone paths of a traditional Cypriot village. Sitting outdoors in the village square amongst a hundred relatives basking in the glory of a traditional home cooked feast. Accompanying my vraka-wearing grandfather to his vineyard to collect grapes as I rode on his donkey. Eating freshly baked bread cooked in a wood fire oven served with olives and home-made haloumi cheese.

In this book I have unearthed the recollections of those who remembered what the island was once like. This very creative generation made the most of what they had. It is not that I am romanticising the past – far from it. Things were undoubtedly tough; poverty, unemployment, malaria, high infant mortality and disease all abounded. However, there existed a powerful connection between people and their community and I believe it is this attribute, that gave Cypriots the strength to survive such hardships. That is the essence of what I am trying to communicate through Tales of Cyprus.

At its core, Tales of Cyprus is also a story of migration, a story of how the Cypriot diaspora has managed to keep the customs and traditions of the past alive. In some cases, I have discovered that the Cypriot diaspora has maintained a more traditional moral code than many who chose to remain on the island. With regards to migration, it is amazing to contemplate how many Cypriots left their island to escape economic hardships or some form of persecution.

Throughout many of the interviews I conducted, there was an underlying sense of loss. I saw many tears and sad smiles. I believe that this grief was for the loss of the life people once knew. For many of my interviewees, this was the first time they had really spoken about their past. Opening up about their homeland was an emotional experience for them. They still missed their villages and loved ones, and they spoke about their past life with such fondness. There was a real sense of nostalgia and even regret for an era that no longer existed.

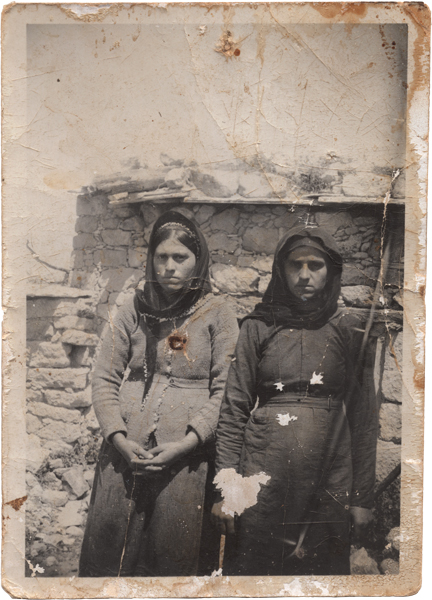

During the initial stages of my ethnographic research, I realised the importance of preserving the images of the past; namely, old family photographs. Each family that I visited had perhaps two or three vintage photographs that had travelled with them from their home. These precious keepsakes are the link between the past and the present. The presence of these photographs in Tales of Cyprus ensures that these images will not be forgotten.

For me, this project has been bittersweet. To be welcomed into peoples’ homes to hear first-hand the accounts of their past lives was a real privilege, always a sweet moment. However, many of the people I met and interviewed were living lonely lives. They didn’t have many visitors to their homes anymore, as many had lost their closest relatives and friends. Their children and grandchildren have their own lives, and are often too busy (or live too far away) to visit. I do try to go back and visit these people whenever I can. As I see it, they are now part of my community.

Tales of Cyprus has evolved into something quite different from its beginnings in 2014. Back then, my intention was to conduct interviews and scan old family photos to help inspire a series of drawings about the past. Along with the drawings, I also created a set of vintage-style travel posters, which formed the basis of my first-ever Tales of Cyprus exhibition in Melbourne. Over 1,500 people came to see my exhibition in December 2014. The majority were from the diaspora – both Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot. It was a wonderful celebration of our combined heritage and intertwined past.

This book was written partly as a response to the public demand that resonated from my weekly posts online and partly from the realisation that there were very few publications of this kind. Any books that did examine Cyprus of old were written in either Greek or Turkish so there was also a need for an English book accessible to younger generations and people of other cultures.

Regardless of whether you have a connection to Cyprus through ancestry or otherwise, this book will appeal to anyone who appreciates how looking towards the past helps make sense of our present – and hopefully improves our future.

I hope the stories that I have documented within this volume provide a nostalgic appreciation of Cyprus of old. I hope they will help to validate the importance of a very special generation of people. Our lives have more meaning and purpose simply because of the sacrifices they have made.

Through these stories and the reproduction of old family photographs, I wish to pay tribute to a bygone era; an homage to a way of life that my parents and their generation knew and had been a part of. I have often said that my parents’ generation will be the last to have lived and witnessed that way of life. That is why I also say that we shall, sadly, never see their kind again.

Tales of Cyprus is also a European story. Many countries in southern Europe have experienced the same breakneck transformation from the past to the present. This catapult into the 21st century can sometimes strip away the authentic cultural landscape of a traditional lifestyle. The Cyprus that my parents knew is now a distant memory. This book recalls that beautiful time in the past through the images and voices of those who experienced it.